Feast Of The Nativity Of Saint John The Baptist (June 24)

(from the writings of Archbishop Alban Goodier, S.J.)

THE COMING OF JOHN THE BAPTIST

It was the fulness of time. That strange, unruly people had waited long. Jericho, as they passed it on their way to and from the Holy City, had stood there through the centuries, to remind them forever of that day when Josue had brought their fathers into the land that flowed with milk and honey. They had entered that land, they had spread over it, they had made it their own, and they had all but perished in it. They had established in it the one God Who had made them His chosen people, they had built His temple on Moria to be the wonder of the world; and yet across the valley to the south was the Hill of Scandal, where he who had built the first temple to their one, true God, had built other temples to other gods in the days of his undoing. They had served their God and had forsaken Him; by Him they had been punished, even to destruction, and yet ever and again the bones of their dead past had been revived. It was a weird tale that they had to recall; a tale of a stiff-necked people, faithless more often than faithful, nevertheless with a something in it that kept it alive, and united, and conscious of itself as the race that must one day save the world.

The city of David had perished, but another had been built on its site. Solomon’s temple had gone, but in its place another had arisen. The very sacred books had been lost but had been found again, and now they were studied as they had never been before. As for their ancient oppressors, Egypt lay buried in its own waste of sand; the Philistines had sunk in the sea; Babylon, Assyria, were names that attached themselves to monster ruins; Antiochus and his Greeks had vanished again as quickly as they had rome. There remained the Romans, the contemptuous, hated Romans; but their day would come, they had sealed their own doom, for had they not violated the Holy of Holies? And there were their myrmidons, the creatures neither Jew nor Roman, Herod and Philip and Lysanias, whom everybody loathed and felt the shame of obeying; surely they had sunk as low as they well could, surely the dawn was at hand. It had always been so; always the Lord had at last remembered mercy; He would do it again.

And yet in what could they hope? They looked at their Temple, gleaming gold beneath the autumn sun, and it filled them with pride; still could they not forget that it had been built, not by Solomon, not by Esdras, but by the bloodstained Herod. Because David had been a man of blood he had been forbidden to build the first temple; how much worse had been Herod!

THE PROPHET ISAIAS

They went into its courts and worshipped; yet had they to close their eyes to much before in His own house they could commune with their God.

They sat at the feet of their teachers and they came away confused. Their scribes bound them down to the letter of the Law; their doctors were divided into schools and confounded one another; their very priests were the puppets of the Roman hand, politic, untrue, grasping, confined now to a single family, with the old man Annas as the guiding star of all. The Law had divorced itself from life; religion had become a binding bondage; men looked with hungry eyes from their city walls towards the eastern hills as the sun rose beautiful above them, and longed and longed again that at length there might come up to them from across the Jordan that other Saviour Who was to bring them light.

That He would come they knew; they could never doubt it. Their whole history foretold it; again and again their prophets had said it; above them all the greatest of their prophets, Isaias. They knew his words by heart; they were steeped in his majestic poetry, his language of mystery they had pondered in their schools.

One passage more than all others they could never forget, so glorious was it, so absolute, so reassuring. Their king that was to be would one day come, so it said, and His herald would announce Him.

‘Be comforted, be comforted, My people, saith your God, speak ye to the heart of Jerusalem and call to her. For her evil is come to an end, her iniquity is forgiven. She hath received of the hand of the Lord double for all her sins.’

Then had the prophet taken his imagery from the grand progresses of the monarchs of old. A runner would go forward to proclaim the king’s coming; mountains would be leveled, valleys would be filled, to make easy his approach.

‘The voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord. Make straight in the wilderness the paths of your God. Every valley shall be exalted and every mountain and hill shall be made low. And the crooked shall become straight and the rough ways plain. And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed. And all flesh together shall see that the mouth of the Lord hath spoken.’

Along that leveled road would come the herald, telling the imminent presence of the king:

Last of all, in might and in meekness, would come the monarch Himself:

‘Behold the Lord shall come with strength, and His arm shall rule. Behold His reward is with Him and His work is before Him. He shall feed His flock like a shepherd. He shall gather together the lambs with his arm. And shall take them up in His bosom. And He shall Himself carry them that are with young.’ (Isaias xl, 1-11).

On words like these men dreamed in and about Jerusalem. At length, in the midst of such a wistful, waiting, hungering world,

‘The word of the Lord came to John the son of Zachary in the desert. And John the Baptist came baptizing and preaching in the desert of Judæa and into all the country about the Jordan preaching the baptism of penance for the remission of sins, and saying: Do penance for the kingdom of Heaven is at hand.’

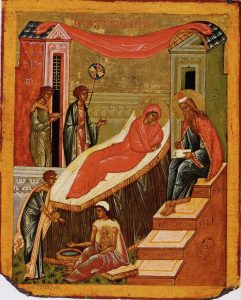

To very many, when he first appeared, John could not have been unknown. There were those who had heard the wonderful things connected with his birth; his father Zachary and his mother Elizabeth were too prominently placed for that event to be easily forgotten. Moreover, the behaviour of John himself had kept it well before them. From the first he had lived his life aloof:

‘And the child grew and was strengthened in spirit, and was in the deserts until the day of his manifestation in Israel.’

He had lived in the deserts of Judæa, yet not so far away but that men might find him if they would; and the fascination of the hermit, the fascination that surrounds all lonely souls, had already drawn men to him.

But now he began to move; he began to assume a new role. Though he clung about the neighbourhood of the city, and still loved the desert places, yet was he often found upon the high roads that passed through them, especially the great main road that led up from the Jordan to Jerusalem. Moreover, his preaching had taken a new turn. Whatever before it had been, now deliberately he proclaimed himself a prophet, a herald of a coming kingdom. He spoke with a new and independent authority; reverent as he was, he assumed a position of his own. He proclaimed a new beginning, repentance for the past, bringing back religion into life; he took hold of the old ceremonial of baptism, as a sign of sorrow, and forgiveness, and reform, and gave it a fresh significance.

It is important here to notice the place which John held in the minds of the people; important because upon it depends much of the action of Jesus in His early public life. While John was prominent on the scene, Jesus bided in the background; only when John was removed, did He come actively forward. The death of John was, it would seem, coincident with the first mission of the twelve Apostles; the last appeal to the Jews in the temple, before Jesus finally left it, was made in the name of John.

1. One evangelist gives to his birth a prominence greater than he gives to that of Jesus Himself. Much more than half of S. Luke’s first chapter is occupied with it; the story of Our Lord’s conception and nativity is more shortly told, and, except for the appearance of the Angels to the shepherds, there is less of the wonderful, more of the commonplace, in the whole narration.

2. Three evangelists point to him as the first great fulfillment of Messianic prophecy, while the fourth lifts him to a rank unique among all the prophets. It would be difficult to speak of any man with greater solemnity than this:

‘There was a man sent from God whose name was John. This man came for a witness to give testimony of the light that all men might believe through him. He was not the light but was to give testimony of the light.’ (John i, 6-8).

3. Lastly Jesus Himself speaks of him in terms which raise him above any other man that has lived.

‘And when the messengers of John were departed, He began to speak to the multitudes concerning John. What went ye out into the desert to see? A reed shaken with the wind? But what went ye out to see? A man clothed in soft garments? Behold they that are in costly apparel and live delicately are in the houses of kings. But what went ye out to see? A prophet? Yea, I say unto you, And more than a prophet. This is he of whom it is written, Behold I send My Angel before thy face who shall prepare the way before thee. For I say unto you among those who are born of women, there is not a greater prophet than John the Baptist.’ (Matthew xi, 7-11. Luke i, 24-28).

Nor was this the only occasion; at another time He spoke of him as ‘A burning and a shining light’,

Nor was this the only occasion; at another time He spoke of him as ‘A burning and a shining light’,

(John v, 35) and yet again as ‘Elias that is to come.’ (Matthew xi, 14).

4. To all this must be added the extraordinary reverence paid to the name of John throughout all this period, which continued steady and unabated even when the Name of Jesus had waned. For instance:

i. On this account, though he held him prisoner, Herod hesitated to execute him:

‘Having a mind to put him to death he feared the people because they esteemed him as a prophet.’ (Matthew xiv, 5).

ii. While he was in prison his disciples never ceased to keep him informed of all that was going on in Galilee:

‘And John’s disciples told him of all these things.’ (Luke vii, 18).

iii. They followed his advice in their attitude to Jesus Himself:

‘John the Baptist sent us to see Thee saying, Art thou He that art to come or look we for another?’ (Luke vii, 20).

iv. After he had been put to death his disciples did honour to his body:

‘Which his disciples hearing they came and took his body and buried it in a tomb and came and told Jesus.’ (Matthew xiv, 12; Mark vi, 29).

v. After his death Herod his murderer lived in constant fear of him:

‘Now at that time Herod the tetrarch heard the fame of Jesus and of all the things that were done by Him and he said to his servants, this is John the Baptist. He is risen from the dead and therefore mighty works shew forth themselves in him. And he was in doubt because it was said by some that John was risen from the dead. But by other some that Elias hath appeared. And by others that one of the old prophets was risen again. Which Herod hearing said, John I have beheaded but who is this of whom I hear such things? John whom I beheaded, he is risen from the dead. And he sought to see him.’ (Matthew xiv, 1, 2; Mark vi, 14-16; Luke ix, 7-9).

vi. At a much later date his evidence for Jesus is quoted in Judæa as being more convincing even than miracles:

‘And He went again beyond Jordan unto that place where John was baptizing first. And there He abode and many resorted to Him. And they said, John indeed did no sign. But all things whatsoever John said of this man were true. And many believed in Him.’ (John x, 40-42).

vii. On the very last day of His public teaching Jesus is able to confute His enemies by an appeal to the baptism of John:

‘For all men counted John that he was a prophet indeed.’ (Matthew xxi, 23-27; Mark xi, 27-33; Luke xx, 1-8).

viii. Years afterwards, when the Church had spread far abroad, disciples of John are still to be met with who,

‘Being fervent in spirit spoke and taught diligently the things that are of Jesus knowing only the baptism of John.’ (Acts xviii, 25).

Though this coming of John need not at first have seemed very remarkable, for others of his kind had from time to time appeared, still there was that about him and his preaching which differentiated him from all the rest. Above all was his method different from that of the spiritual leaders whom the men of Judæa had been wont to follow. These came before them particular in their dress, their fringes and their phylacteries, conforming with exaggerated detail to their interpretation of the Law. He discarded all this; he would not even heed common convention. He would clothe himself with just that which came first to hand; he would eat just that which nature placed within his reach in the wilderness, and nothing more.

‘And the same John had his garments of camel’s hair and a leathern girdle about his loins. And his meat was locusts and wild honey.’ (Matthew iii, 4).

His preaching, too, was different. Their guides taught them the details of the Law and its minute obligations placing in their observance the height of sanctity. John never mentioned these; he broke right through them and dived into the very hearts of men. He appealed to their inner knowledge of themselves, of right and wrong, of good and evil, truth and falsehood. If they would have ceremonial, then let it be such as declared the soul, true acknowledgment of evil done, true reform of life, true preparation for whatever was to come.

Preaching such as this soon began to tell. Travelers up to Jerusalem, merchants from the East, pilgrims coming to the festivals, would look at this strange figure, and listen for a while, and pass by. They might affect to disregard him; they might call this man but another fanatic revivalist; they might say the things he taught were of no concern to them; busy, preoccupied as they were, they might resent the intrusion as unwarranted, vulgar, unseemly. Still would the chance words they heard refuse to leave them; they had pierced their hearts and their consciences and would not be quieted. These men went on their way they talked among themselves; they linked this teaching up with the teaching of the Law, and saw that it gave the Law new life. Gradually they came back, bringing other with them; some only curious to see this new phenomenon some in timid hope that here might be a new beginning; some, who had hungered for long years, seeing already in this sudden revelation a sign that the day of salvation was at hand. They came and they were conquered; they came to learn and they discovered themselves. From the city they came and from the hill country round about; they would not return till by an open avowal they had confessed their belief in this man.

‘Then went out to him all the country of Judaea, and all they of Jerusalem, and all the country about Jordan. And they were baptized by him in the river Jordan confessing their sins.’

Such a movement could not fail soon to attract those in authority, the guardians of the Law, the doctors in Israel, the men who, first among all, were to recognize and welcome the Messias when He came. They knew the signs, they interpreted the prophets; when they were fulfilled it would be for them to judge; in the meantime they were the masters, of Israel and of its Temple. Of course this John, whoever he might prove to be, must never be allowed to interfere with their prerogative. On the other hand so long as there was no sign, and little fear of that, he might be countenanced; out of such revivals usually grew a greater observance in the Temple. They would go down to him themselves; they would support the movement by their presence; by their own submission to this ceremonial of the Baptist they would give it a mark of their approval. In this way at least they would keep a hold upon this new preacher, whom already it might be dangerous to oppose.

But the Baptist was not to be deceived. Not for nothing had he spent his years of preparation in the desert, studying men, learning men as only he can learn them who leads his life apart, sifting the truth from the falsehood of their ways. Not for nothing had he searched the Scriptures, and separated grain from chaff. The specious defence that these people held up before themselves, that they were the children of Abraham, that they were the chosen of God, that they were therefore secure from rejection, must be broken down if the ‘way of the Lord’ was to be made straight. Plainly and at once they must be told of their crafty nature, of their blind self-deception, of the emptiness of their claim. If they would rightly inherit their birthright there must be truth to the core; there must be a renewal of the inner man, there must be no make-belief, no substitute of outward show for sincerity. The fruits they produced must be from themselves, not from the hollow fulfillment of a hollow Law.

He spoke alike to all, but it was to the Pharisees and scribes mingled with the crowd that his words were specially addressed. Mercilessly he spoke to them; from the beginning there should be no mistake. After submission of heart, the one great mountain to be leveled before the Lord could come to His Own was the hardened refuse piled up and trodden down about the Law.

‘And seeing many of the Pharisees and Sadducees coming to his baptism he said to the multitudes that came forth to be baptized by him, Ye brood of vipers. Who hath shewed you to flee from the wrath to come? Bring forth therefore fruits worthy of penance. And think not, do not begin to say within yourselves we have Abraham for our father. For I say to you that God is able of these stones to raise up children to Abraham. For now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree therefore that bringeth not forth good fruit shall be cut down and cast into the fire.’

Language such as this was not to be mistaken. From the outset John threw down the gauntlet, refusing to parley; it was a declaration of war with a definite enemy, which was to end only on Calvary.

The people heard, but the significance of the challenge passed them by. They were too much concerned with themselves to take much heed of the Pharisees and Scribes; it was enough for them that the Baptist taught the need of ‘fruits worthy of penance.’ They asked for further light and guidance. They were a motley crew, for the most part men of no particular religious reputation; common men, tax-collectors bearing an ill name, soldiers restless and discontented, whose power and position gave them opportunity for every kind of evil, poor folk from the country-side, not over-burthened with intelligence, still more wanting in instruction, whose hard lives had closed their hands to their neighbours and had killed in them the first elements of love. But they wished to rise to better things; and here was one who would teach them how they might do it. They asked him, and to them John altered his tone; treated them tenderly as sheep that had no shepherd; imposed on them no burthen heavier than they could bear; simply, in language of their own, told them just the duties of their state of life. In these last words of counsel there is a gentleness and sympathy of nature which goes far to explain the hold of John upon the people; it is an anticipation of Him Who ‘Would not crush the broken reed and smoking flax would not extinguish.’

‘And the people asked him saying, What then shall we do? And he answering said to them, He that hath two coats, let him give to him that hath none. And he that hath meat, let him do in like manner. And the publicans also came to be baptized and said to him. Master what shall we do? But he said to them, Do nothing more than that which is appointed unto you. And the soldiers also asked him saying, And what shall we do? And he said to them, Do violence to no man. Neither calumniate any man. And be content with your pay.’

Can we now picture to ourselves this first appearance of the Baptist? He came into a world with an ancient tradition, with a belief, a conviction, that a great future lay before it, yet were both tradition and belief marred by the dross that had gathered round them. He came among men intent upon their own affairs, especially their own political affairs, in consequence suspicious, self-centred, prone to hatred. Religion for them was a rigid, stereotyped substitute form; against its claims and ever-growing tyranny many had long since begun to chafe, though they could not lay aside the old inheritance, nor rid themselves of its ceremonial, nor reject altogether the hope in the future which it gave. He came at a time when many, eager souls as well as souls that feared, were on the tip-toe of expectation, strained so far that they were in danger of despair. He came and stood in the desert by the river, at the gateway leading into Judæa, on the very spot that was still hallowed by the memory of the prophet Elias, hard upon the main road along which the busy world had to pass; a weird, uncouth, unkempt, terrible figure, in harmony With his surroundings, of single mind, unflinching, fearing none, respecter of no person, asking for nothing, to whom the world with its judgments was of no account whatever though he showed that he knew it through and through, all its castes and all its colours. He came the censor of men, the terror of men, the warning to men, yet winning men by his utter sincerity; telling them plainly the truth about themselves and forcing them to own that he was right; drawing them by no soft inducements, but by the hard lash of his words, and by the solemn threat of doom that awaited them who would not hear; distinguishing true heart-conversion from the false conversion of conformity, religion that lived in the soul from that sham thing of mere inheritance and law; going down into the depths of human nature in his ceaseless search for ‘the true Israelite in whom there was no guile’; an Angel and no man, fearless voice to which the material world seemed as nothing compelling attention, fascinating even those who would have passed him by, making straight the path through the hearts of men; cleansing, baptizing, pointing to truth, life, but as yet, until all was prepared, saying nothing of that Lord Whose corning he was sent to herald, content to foretell only the Kingdom; John, the focus upon which all the gathered light of the Old Dispensation converge, from which was to radiate the light of the New. All this those felt who now began to ask, concerning themselves: What then shall we do?’ concerning him: ‘Who is he?’—crowds of every kind, publicans, soldiers, citizens from the great towns and country villages, patronizing Pharisees and submissive disciples.

Can we now picture to ourselves this first appearance of the Baptist? He came into a world with an ancient tradition, with a belief, a conviction, that a great future lay before it, yet were both tradition and belief marred by the dross that had gathered round them. He came among men intent upon their own affairs, especially their own political affairs, in consequence suspicious, self-centred, prone to hatred. Religion for them was a rigid, stereotyped substitute form; against its claims and ever-growing tyranny many had long since begun to chafe, though they could not lay aside the old inheritance, nor rid themselves of its ceremonial, nor reject altogether the hope in the future which it gave. He came at a time when many, eager souls as well as souls that feared, were on the tip-toe of expectation, strained so far that they were in danger of despair. He came and stood in the desert by the river, at the gateway leading into Judæa, on the very spot that was still hallowed by the memory of the prophet Elias, hard upon the main road along which the busy world had to pass; a weird, uncouth, unkempt, terrible figure, in harmony With his surroundings, of single mind, unflinching, fearing none, respecter of no person, asking for nothing, to whom the world with its judgments was of no account whatever though he showed that he knew it through and through, all its castes and all its colours. He came the censor of men, the terror of men, the warning to men, yet winning men by his utter sincerity; telling them plainly the truth about themselves and forcing them to own that he was right; drawing them by no soft inducements, but by the hard lash of his words, and by the solemn threat of doom that awaited them who would not hear; distinguishing true heart-conversion from the false conversion of conformity, religion that lived in the soul from that sham thing of mere inheritance and law; going down into the depths of human nature in his ceaseless search for ‘the true Israelite in whom there was no guile’; an Angel and no man, fearless voice to which the material world seemed as nothing compelling attention, fascinating even those who would have passed him by, making straight the path through the hearts of men; cleansing, baptizing, pointing to truth, life, but as yet, until all was prepared, saying nothing of that Lord Whose corning he was sent to herald, content to foretell only the Kingdom; John, the focus upon which all the gathered light of the Old Dispensation converge, from which was to radiate the light of the New. All this those felt who now began to ask, concerning themselves: What then shall we do?’ concerning him: ‘Who is he?’—crowds of every kind, publicans, soldiers, citizens from the great towns and country villages, patronizing Pharisees and submissive disciples.